Katharine Hepburn was a star, of that there was no question – but a star unlike any other in Tinseltown. She broke all the rules and, in doing so, wrote herself into movie legend. While the aspirational women of Hollywood had curvy, hourglass figures enhanced by silk and satin couture, boyishly slim Kate Hepburn sported comfortable trousers and shapeless sweaters. Feisty in an age when women were still supposed to be passively beautiful, she had a fine brain and used it.

Katharine Houghton Hepburn was born on May 12, 1907, in Hartford, Connecticut, to a doctor and a suffragette, both of whom always encouraged her to speak her mind, develop it fully, and exercise her body to its full potential. She idolised them both and, in her autobiography Me, she paid tribute to them, even though they were long-dead. “What you did for me – Wow!” she wrote. “What luck to be born out of love and to live in an atmosphere of warmth and interest.”

The young Katharine was well-educated, attending the elite Bryn Mawr college in Pennsylvania, where she was taught to think for herself. And it was here that she caught the acting bug, appearing in many of the school productions.

While at Bryn Mawr, she had met Ludlow Ogden Smith, a man of a similar social background to hers. He changed his name to Ogden Ludlow because Katharine couldn’t bear the idea of becoming Mrs Smith and, aged 21, she married him and moved to Pennsylvania. Three weeks later she was back. The marriage fell apart – Kate’s fault, she accepted – and six years later they were divorced, though they remained lifelong friends.

Katharine’s theatre career was slow to get going – this red-haired, freckled girl was not what Broadway was used to – but, at the age of 24, Kate made her mark in The Warrior’s Husband, playing an Amazon who, show-stoppingly, ran down a steep staircase carrying a stag across her shoulders. Hollywood picked up on her success and offered her a screen test for A Bill Of Divorcement. Offered the role, she feigned indifference and said she would only do it if paid $1,500 a week. She got her deal.

In the same year came Little Women and Morning Glory, which brought the first of her four Oscars in 1933. Her co-star, Douglas Fairbanks Jr, said he fell instantly in love with her. “I had a particularly big crush on her. Of course, I would have been a deal fool if I hadn’t.” He remembered taking her home and staying in his car after she had gone into the house: “and the next thing I saw out of the corner of my eye, at the back of the house, running through to another street, was the little figure of Kate dashing out – and going off somewhere into someone else’s car. I never knew who it was.”

The mysterious suitor was one of dozens who pursued the actress through the Thirties. She had an affair with eminent agent Leland Hayward, another with millionaire Howard Hughes – who taught her to fly and bought her the rights to The Philadelphia Story – and yet another with John Ford. At first sight, Ford – a director of action films like Stagecoach starring his protégé John Wayne – was a strange choice for a sophisticate like Kate. He was also married. They struck sparks off each other. He once told her to come into the studio in a dress, “like a lady”. She promised to do so – when he came to work as a gentleman.

Her mannish dress and independent ways had sparked rumours about her sexuality when she first came to Hollywood, and she was never the conventional Tinseltown sex goddess. But she was, in her own high-cheekboned way, quite exquisite. In the marvellous 1940 hit The Philadelphia Story Kate finally succumbed to Cary Grant. But it was displaying her coquettish, vulnerable side opposite James Stewart that she revealed a sex appeal many men had never known was there.

It was the nine films she made with Spencer Tracy, however, that established the public persona that both reflected and masked her real self. It started with1942’s Woman Of The Year and finished up with Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner?, a quarter of a century later. Surprisingly, considering Katherine’s famed independence, having fallen hook, line and sinker for the funny, fearsomely talented, but irascible Spencer, she felt what he wanted, what he needed and what he demanded came first.

It might have disappointed admirers of her sassy screen image, but at 33 Kate had found the real thing, the love that had eluded her through all her other relationships, fun though they had been. “It seems to me I discovered what, ‘I love you’ really means,” she wrote. “It means I put you and your interests and your comfort ahead of my own interests and my own comfort, because I love you.”

It meant sacrifices. Tracy was absolutely simple and centred on screen, but in real life he was a complicated man, tortured by guilt and unknown demons that sent him too often to the bottle. They were together, in secret, for 27 years. They never married. Spencer was a Catholic and would never divorce, though he was often unfaithful, both to his wife Louise and to Kate. Spence died just days after Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner? was completed and Kate was there at the bitter end, although she quickly absented herself after his demise, once she had alerted their friends.

Kate stayed away from the funeral, out of respect for his widow, but later phoned Mrs Tracy to offer a friendship she hoped they both could live with. It was a gesture that was not appreciated. “I thought you were just a rumour,” said the widow.

The pain of Spencer’s death never left Katharine. At home in her brownstone terraced house in New York, her favourite chair was placed underneath a giant painting of her lover. It remained there for the rest of her life, a memorial to what was, in Hollywood terms, a unique relationship.

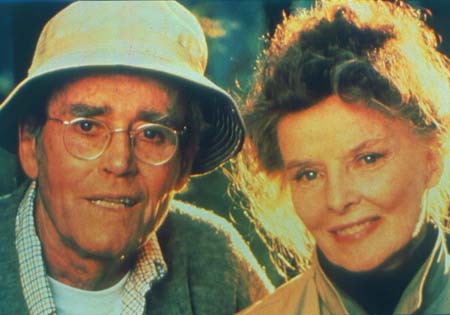

After Spencer’s death, Katherine kept herself busy, winning her third Oscar for her performance in The Lion In Winter. In it, she matched Peter O’Toole point for point in a way that had recalled her best against Tracy, or against Humphrey Bogart in 1951’s The African Queen. She was a match for any leading man and, in 1975, she matched up for the first time with two actors who gave her a chance to show just how wide her range could be: John Wayne in Rooster Cogburn and Lord Olivier in the TV movie Love Among The Ruins.In 1981 there was another first-time pairing in On Golden Pond. It was actually the first time she and Henry Fonda had met – “It’s about time,” she said as they shook hands. Fans loved this story of an elderly couple leaving their summer home for what was probably going to be the last time. Henry Fonda won his first acting Oscar posthumously; Kate won her fourth, to go with her other eight other nominations, a record of a remarkable career.

At Fenwick on Long Island Sound, where she had spent her summers since early childhood, Katharine lived at the family house, rebuilt after the hurricane of 1938, with her brother Bob and her small entourage. In her eighties, she wrote with pleasure that she had been drinking the night before with a man who had been her three-legged race partner over 70 years ago. Until very old age, she could be seen cycling along the country lanes there. Above all, she liked to swim off its beaches. “I love swimming,” she said, “it makes you feel clean.” A perhaps not surprising statement from a woman who took a bath sometimes seven times a day.

Katharine had never liked random strangers very much, people whom she always suspected just wanted to sightsee. A notice on the door of her property proclaimed: “Please go away”. And that was how she finally told producers she was not going to do any more work. She was never going to play pathetic old ladies, she said. “I’m not marvellous or something like that. I’ve just worked damn hard for a very long time and done the best I could.”

Photo: © Alphapress.com

Photo: © Alphapress.com

Photo: © Alphapress.com

Photo: © Alphapress.com

Photo: © Alphapress.com

Photo: © Alphapress.com

Photo: © Alphapress.com

Photo: © Alphapress.com